Microbes are all around us. In terms of numbers they rule the earth, and they manage to live under extreme conditions, such as in hot springs, in polar ice, at depth in rock formations, and in any conceivable environment in between. Of interest for this paper are microbes that colonize, stabilize, and modify the surfaces of sandy and muddy sediments. Microbial mat deposits in carbonates are excluded, although the vast majority of published examples is found in that rock type.

Modern microbial mats on sandy sediment surfaces are well documented. The microbial colonization of muddy surfaces, although less known, can be readily observed in modern puddles a few days after a rainstorm. Essentially, for any sedimentary surface there is likely a microbial community that is equipped to thrive there if sedimentation rates are sufficiently small. Some can even prosper in absence of sunlight, or in the harsh and dry conditions of deserts.

Considering how many times the "present has been the key to the past", it stands to reason that numerous ancient sand and mud surfaces were colonized by microbial communities. Thus, we may assume that sandstone and mudstone deposits of the geologic record should abound with microbial mat deposits

It is at this point that an old geologic truth asserts itself once again: "just because something should have existed does not mean that it has been preserved". Positively proving the former presence of microbial mats in sedimentary rocks of any kind is actually quite a formidable task. Even in modern microbial mat systems, all remnants of the constructing microbiota may be destroyed within the first few hundred years of burial. Furthermore, if one applies strict criteria of biogenicity, such as preserved filaments in live position to published examples of fossil microbial mats (or stromatolites), only a very small portion can actually be shown to have a clearly demonstrable organosedimentary origin.

So, what is a sedimentologist to do? Simply play it safe and assume that a given laminated sediment is not of microbial origin because proof positive is missing? Maybe we should look at the question from a different angle. In trace fossils, for example, the animal that produced the fossil is typically not preserved in association with the burrow. There is no dispute, however, that the traces were produced by a variety of animals, and that traces can be considered "fossilized behavior". As these animals were searching for food or seeking shelter, they invariably modified the sediment and produced trace fossils that record the interaction of the animal with the sediment. Likewise, laminated sediments produced by microbial mats can be considered the "trace" that reflects the interaction of the mat community with the environment.

Microbial Mats in Mudstones (and sandstones)

Unfortunately, laminated sediments can just as well be produced by purely physical sedimentation processes. Thus, there is a need to develop criteria for the identification of microbial mat laminae. The best place to start looking for microbial mat deposits in sandstones and mudstones is the Proterozoic. Its biosphere was dominated by microorganisms and the bulk of all published microbial mat deposits (stromatolites), albeit in carbonates, come from that time period. In the Phanerozoic, of course, bioturbation and grazing had a negative impact on the preserved biomat record. Nonetheless, if one starts looking around, one finds that even today, microbial films and mats abound in many sedimentary environments. In fact, it is hard to look at many aqueous environments without finding that sediment particles and sediment surfaces in many instances carry microbial communities. The resulting bio-films render the surface slippery (as most of us know from experience), bind particles together, and change the chemistry of the underlying sediments.

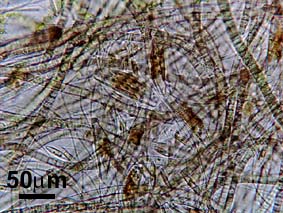

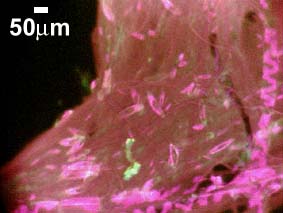

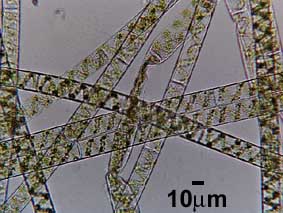

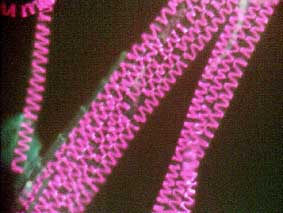

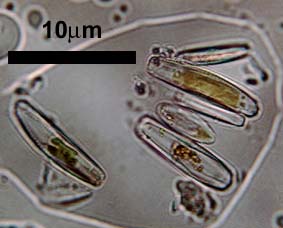

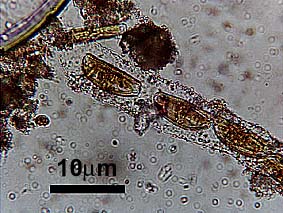

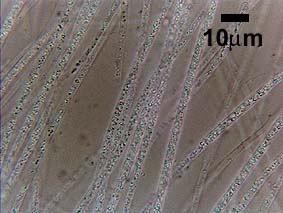

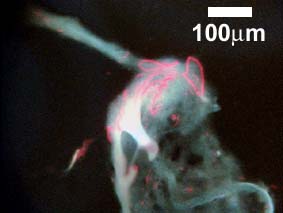

Just for entertainment purposes I am showing in the space below microbial features that I noticed along a small stream near Sulphur, Oklahoma. Although streams are normally not thought of as suitable habitats for microbial mats, in this particular case we are dealing with a spring fed stream that has only a small suspended sediment load (would have negative impact on mat).

Within this stream, and especially close to the origin of the springs, the entire stream bed may be covered with microbial covers that can reach several mm thickness, and may show morphologies reflective of flow conditions.