Research Interests

Shales are my passion. They constitute approximately two thirds of the sedimentary column on Earth, and are nonetheless the least understood sedimentary rock type. The lion's share of the sedimentary rock record consists of shales and mudstones. Although still only a footnote in most soft rock curricula, there are a number of very good reasons to study shales and mudstones.

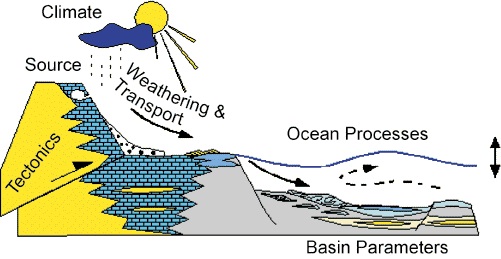

First, in order to read the rock record correctly and at the highest detail possible, we have to learn how to "read" shales. Understanding their deposition is key to the reconstruction of past oceans, landscapes, climates, and climatic cycles. Yet, whereas students of sandstones and carbonates have been able to learn a great deal about the deposition of these rocks from studying bedforms and sedimentary structures in the context of experimental data and direct observations in modern environments, the situation is not as fortunate when we examine our current knowledge concerning shales and mudstones. The situation is changing rapidly, however, driven in part by the flume research that we are conducting at IU.

Second, regardless whether they contain a fraction of a percent or several ten percent of organic matter, mudstones and shales are the source of the hydrocarbons that fuel the world economy. Furthermore, the seals that keep hydrocarbons in their reservoir, protect groundwater resources, and contain dangerous industrial waste products are all made of the same stuff - shales and mudstones. And finally, the technological advances in horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing have made it feasible to exploit the vast hydrocarbon reserves (gas and even liquids) that are stored in carbonaceous shale units in the US and elsewhere. This new reality has changed the study of shales from an academic past time to a matter of utmost economic importance.

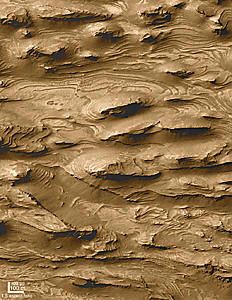

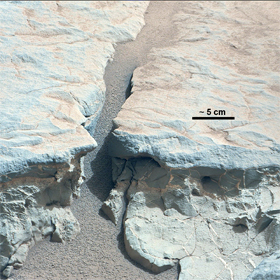

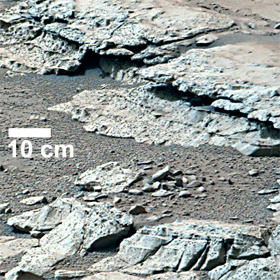

Third, shales are not restricted to the planet Earth. Several years ago evidence of layered rocks that show differential weathering of soft vs hard strata was discovered on Mars (Malin, M.C., and Edgett, K.S., 2000, Sedimentary rocks of early Mars, Science, v. 290, p. 1927-1937). Considering that much of the Martian sediments were derived from weathering of basalts, it is not a stretch to expect that the soft weathering intervals of Martian stratigraphy are clay dominated and consist of rocks that on Earth would be called mudstones. The 2004 MER rovers also brought us images of sediment layers that are so fine grained that they are probably mudstones, and images of flaky weathering sediments that on Earth would most likely be identified as a shale or shaley siltstone. Finally the latest rover to explore Mars, Mars Science Lab/Curiosity that touched down in August 2012, has located bona fide mudstones just 450 m distant from its landing site and is now en route to a location where we hope to find more mudstones and also sedimentary sulfate/evaporite deposits. At the moment the rover is traversing rough terrane to reach that locality, probably in the Fall of 2014.